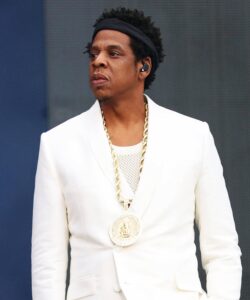

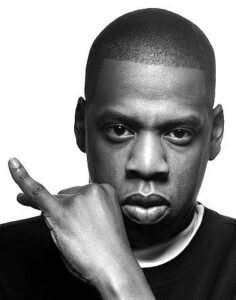

When Shawn Carter, known to the world as Jay-Z, says he built an empire, he means it literally. The story that started in Brooklyn’s Marcy Houses and in mixtape racks has, over three decades, grown into a portfolio that reads like a blueprint for how culture can be turned into capital. He is still very much an artist, but he runs businesses like a strategist, placing bets where culture meets luxury, tech, and sport. He is one of music’s richest figures, a billionaire whose wealth today is as much from drinks and stakes as it is from records.

The pivot that changed everything came not from a studio but from a bottle. Jay-Z bought Armand de Brignac, the Ace of Spades champagne, and pushed it into the spotlight the way only a pop-culture icon can. In 2021 he sold half the brand to LVMH’s Moët Hennessy. The deal did two things. It validated a luxury brand built on cultural currency, and it showed the logic behind celebrity-led premium goods, where a story and cachet can trump decades of heritage. That move, and his long-standing partnership with Bacardi on D’Ussé cognac, transformed liquor into one of his most reliable revenue engines.

But Jay-Z’s playbook is not “buy and exit.” It is about building ecosystems. Roc Nation started as an artist management and creative agency and then became a wider entertainment company handling music, touring, sports, and branded content. Roc Nation’s deal-making, from managing talent to striking partnerships with major sports leagues, shows that the firm’s value is in combining content, talent, and rights in ways legacy companies did not. That integrated approach is why Roc Nation often acts less like a label and more like a modern media holding company.

There have been stumbles. Tidal, the streaming service Jay-Z bought and relaunched as an artist-first platform, never dethroned Spotify or Apple Music. In 2021, Square, the payments group led by Jack Dorsey, acquired a majority stake in Tidal. For Jay-Z the deal was tactical. It tied music to payments and fintech possibilities that could give artists new revenue mechanics. The lesson was not that streaming failed, but that media ventures need capital partners who offer more than money. They must bring distribution and product capabilities, particularly in a winner-takes-most streaming market.

Jay-Z’s investment arm, Marcy Venture Partners, is another piece of the puzzle. The fund has focused on startups and founders, often backing firms in fintech, media, and marketplaces that mirror Jay-Z’s own interests in ownership and infrastructure. In late 2024 Marcy merged with another Black-owned investment firm, expanding its reach and signalling a shift from celebrity cheque-writing to institutionalised, long-term capital. That is a turning point. It shows celebrities are no longer just brand ambassadors for other people’s funds. They are building permanent financial institutions that can scale and survive market cycles.

What ties these moves together is taste. Jay-Z’s edge is cultural curation coupled with hard negotiation. He sells exclusivity to millions, whether through high-end champagne, premium streaming quality, or talent deals. But he also knows when to partner and when to hand over control. Selling half of Armand de Brignac to LVMH, or accepting Square as Tidal’s majority owner, were not retreats. They were calculated swaps: culture and brand in return for distribution, manufacturing muscle, and capital. That trade-off is the modern celebrity’s runway to scale.

There are risks. Luxury alcohol depends on discretionary spend cycles and shifting tastes. Media bets require patient capital. Celebrity reputation always matters. Yet Jay-Z has navigated those dangers by diversifying across asset types, buying into categories with high margins and strong brand effects, and building teams that understand both commerce and culture. He has also used real estate, sports equity, and strategic exits to lock in gains and reinvest them.

For global business readers the takeaway is simple. Jay-Z’s model shows how intellectual property, credibility, and network value translate into market value when paired with the right corporate partners. His moves matter because they point to a roadmap for creators who want to be owners. In an age where attention is the raw material, Jay-Z has turned attention into equity, and then into institutions.

If there is a final note, it is this. He treats culture like capital and capital like culture. That is why boardrooms now look to artists for playbooks on brand, and artists look to businesses for lessons in scale. Jay-Z did not invent that loop. He monetised it, and then taught the market how valuable that lesson can be.